Ok, Boomer! Generational Wealth and The Way of All Flesh

Samuel Butler's Novel Explores How and Why to Pass Down Money to the Young

I just finished one of the minor classics on my bucket list, Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh. I found it very funny, but far less biting than I presume Edwardian readers did on its publication. The original audience, after all, came of age in the Victorian era that Butler satirizes. But to a modern reader, his caustic takes on religion and middle class values can seem trite. Attacking Christianity as irrational and its followers as hypocritical? That’s been done a million times over by now.

Yet there’s one theme in The Way of All Flesh that remains surprisingly fresh: money. Specifically, how and why wealth is passed from one generation to the next.

Butler was heavily influenced by 19th-Century evolutionary theory and applies it (awkwardly, in my opinion, as I’ll explain later) to the saga of the Pontifex family. In Butler’s view, money — and the lack thereof — is one of the most powerful influences upon a child’s ability to adapt to the world. Used rightly, it provides an environment to encourage all the best aspects of a child’s inborn temperament. Used wrongly, it either allows the child to indulge the worst parts of his nature, or completely ignores the child’s nature in favor of total parental control (for better or for worse).

Everything depends, then, on money being in the hands of the right guardian, one who recognizes when to turn on the spigot and when to keep it shut. But in a fast-changing world, how does an elder know when to help and when to withhold (especially when withholding means watching your child struggle)? How does a parent decide whether to give freely or with strings attached?

The Way of All Flesh explores potential answers to these questions, both disastrous and ideal.

Disastrous: Giving Based on Conventional Wisdom and a Thirst for Control

Generational wealth as force of influence first comes into play through George Pontifex, grandfather of the novel’s protagonist, Ernest Pontifex.

George has a head for business, becoming an apprentice at his uncle’s publishing house at a young age and eventually taking over the firm entirely. He builds his wealth churning out middling Christian books with titles like The Pious Country Parishioner (as well as marrying a woman with a handsome inheritance).

Butler has a gleeful time using George to send up Victorian mores like the Grand Tour and Romantic poetry. George is mercantile and money-grubbing, without an artistic bone in his body. Yet as Butler relates, his “first glimpse of Mont Blanc threw Mr. Pontifex into a conventional ecstasy,” prompting him to write in his diary: “My feelings I cannot express. I gasped, yet hardly dared to breathe, as I viewed for the first time the monarch of the mountain.” And despite being purportedly struck wordless, he composes some gushing couplets about the scenery in a Swiss chateau’s guest book.

What inspires a non-aesthete like George to (try to) parrot Shelley? Butler’s answer is conventional wisdom. George unthinkingly equates an affinity for Romantic poetry with being highly cultured and modern, since his fellow Victorians did as well. He reacts to nature by spouting cringeworthy Romantic verse because the influencers of his day signaled that that was the thing to do. Or as Butler more bitingly puts it:

[George] had made up his mind to admire only what he thought it would be creditable in him to admire, to look at nature and art only through the spectacles that had been handed down to him by generation after generation of prigs and imposters.

Conventional wisdom also explains why George, the would-be poet and publisher of Christian tracts, routinely beats his children:

Mr. Pontifex may have been a little sterner with his children than his neighbors, but not much. He thrashed his boys two or three times a week, but in those days fathers were always thrashing their boys.

More pertinent to this post, conventional wisdom explains why George forces his son, Theobald, to become a clergyman by threatening to withhold all financial support otherwise. As Victorian pater familias, George assumes —as so many of his fellow parents did — the right to choose Theobald’s profession (and besides, since George publishes Christian books for a living, he reasons having a clergyman in the family couldn’t hurt business). He wields this control through generational wealth, combined with the self-aggrandizing guilt trips he directs at his sons, such as this beauty:

Pray don’t take it into your heads that I am going to wear my life out making money so that my sons may spend it for me. If you want money you must make it for yourselves as I did, for I give you my word I will not leave a penny to either of you unless you show that you deserve it . . .

Young people seem nowadays to expect all kinds of luxuries and indulgences which were never heard of when I was a boy. Why, my father was a common carpenter and here are both of you at public schools, costing me ever so many hundreds a year, while I at your age was plodding behind a desk in my [Uncle’s] counting house. What should I not have done if I had had one half of your advantages!

. . . No, no, I shall see you through school and college and then, if you please, you will make your own way in this world.

Maybe I’ve been online too much (okay, I’ve been online way too much), but when I read George’s rant a little voice in my head responded: Ok, Boomer. After all, George’s iron grip over the family purse? His not-quite-honest valorization of himself as a self-made man while ignoring the economic challenges his children face? Not to mention his dismissal of his son’s desire to, you know, actually like his career? These are behaviors, rightly or wrongly, characterized as “Boomer” and pilloried by Millennials and Gen Z.

As a college fellow, with his ordination approaching, Theobald realizes he has no calling for the clergy. He writes to George, asking to forego ordination and instead work as a tutor until he can find another profession. George’s reply isn’t far from that of a modern parent responding to a child who, having completed nearly all the coursework for a business degree, suddenly balks at that finance job Dad has lined up for him:

Nothing has been spared by me to give you the advantages . . . I was anxious to afford my son, but I am not prepared to see that expense thrown away and to have to begin again from the beginning, merely because you have taken some foolish scruples into your head . . .

In other words, enough with this “follow your bliss” bullshit! It’s called work for a reason, and it’s high time you knuckled down and earned a decent paycheck instead of holding out for “fulfillment”!

After some back-and-forth, George ultimately declares that if Theobald isn’t ordained, he “shall not receive a single sixpence more” from him. That settles it: Theobald swallows his misgivings and, despite being thoroughly unsuited for it, becomes a parish priest (and predictably, he’s terrible at it).

Authoritarian that he is, you have to feel for George here. A curacy in a nice parish was a steady living, and besides, Theobald didn’t make a peep about being forced into the clergy until just before his ordination!

Yet Butler makes clear that this dilemma was created by George himself. Years of George’s thrashings and abusive diatribes crushed Theobald’s ability to think for and defend himself. While a stronger son may have resisted George’s will, Theobald could only “dully acquiesce” to it, to the point he couldn’t know his own mind:

He may have had an ill-defined sense of ideals that were not his actuals; he might occasionally dream of himself as a soldier or sailor far away in foreign lands, or even as a farmer’s boy upon the wolds, but there was not enough in him for there to be any chance of his turning his dreams into realities, and he drifted on with his stream, which was a slow, and, I am afraid, muddy one.

The foregoing illustrates the thorny problem George himself created: Without Theobald knowing his own mind, it’s not certain any amount of family money handed to him will be of use. Instead, Theobald risks flitting from one school/degree/job to the next, always chasing phantom satisfaction.

But if knowing oneself is a precondition for receiving generational wealth, where does that leave the young adults who haven’t yet figured out who they are and what they want out of life (and in my observation, that’s a sizable number of young adults)?

Butler answers this question through Ernest Pontifex.

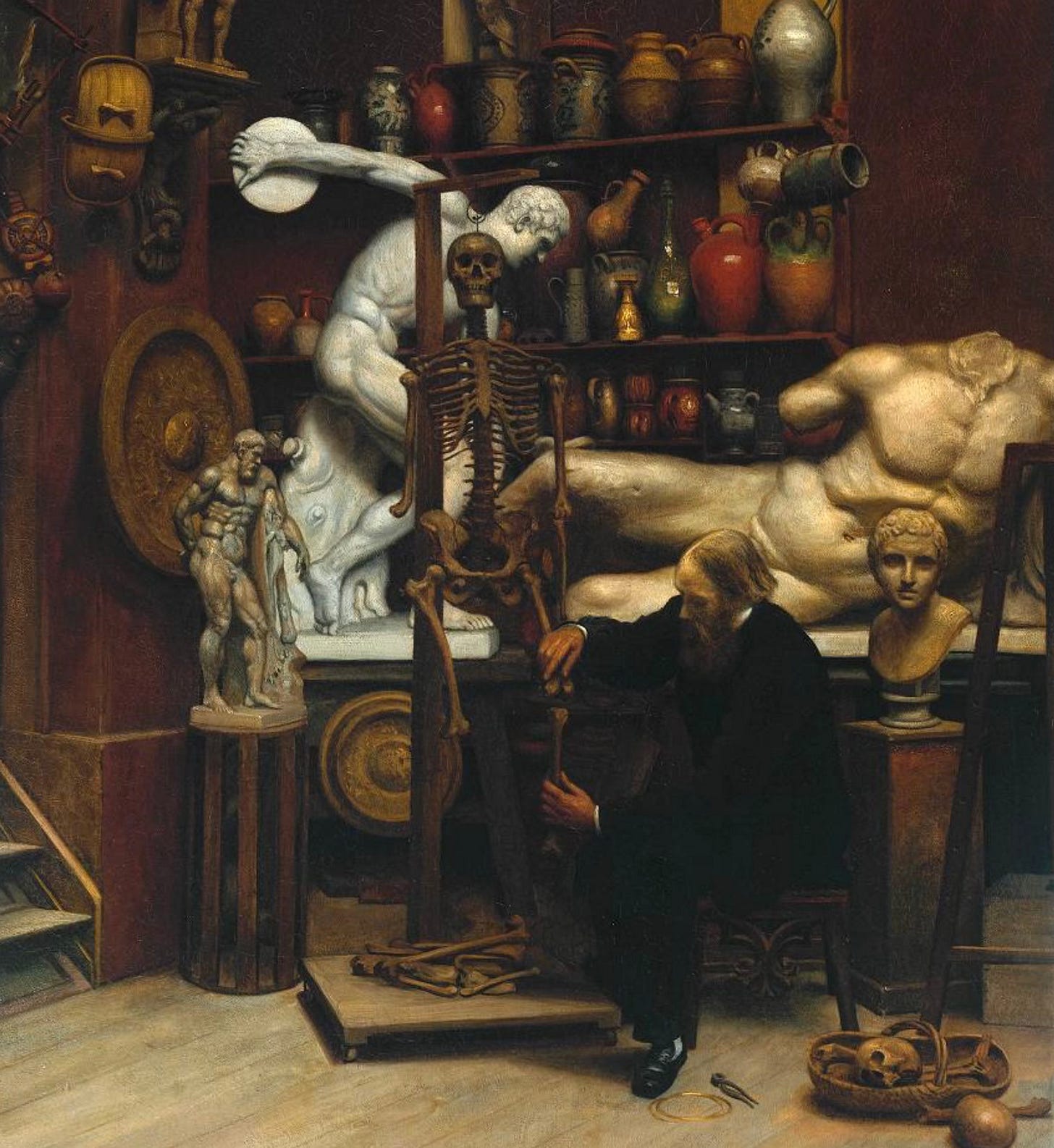

(Above is one of Butler’s oil paintings. He was a talented artist and, unlike Theobald and Ernest Pontifex, defied his father to pursue a painting career instead of one in the church.)

Ideal: Timing Money to Promote Optimal Growth … Even If That Means Watching Your Kid Suffer

Theobald proves to be just as overbearing a father to his son Ernest as George was to Theobald (bringing to mind Philip Larkin’s observation that “man hands on misery to man”). He raises Ernest to consider himself sinful and inferior in comparison to Theobald, and, like George, relies on beatings to discipline Ernest and squelch any hint of autonomy.

Predictably, Ernest comes of age in years only, so accustomed to acquiescing to his parents and elders that he’s unable to truly think and act for himself. Mercifully, though, Butler provides an alternative vision of parenting via Ernest’s Aunt Alethea and his godfather, Overton. Both these characters endeavor to foster the best of Ernest’s inborn traits - his lively intellect, his affinity for music and writing - by molding his environment. And their primary tool for molding his environment is — surprise, surprise — money.

Alethea first becomes a substitute parent to Ernest when he attends boarding school in Roxborough. At that point, the unmarried and childless Alethea is contemplating to whom she’ll leave her fortune. After treating Ernest to dinner and loosening his tongue with glasses of sherry, she’s delighted to find that he disdains his stodgy headmaster and shows an appreciation for classical music far beyond his years.

And so, in a leap of faith, she moves to Roxborough and begins to build an environment for Ernest to nurture his hidden talents. She surrounds him with the brightest and most gentlemanly of his classmates. She arranges for Ernest to help build an organ for the school’s chapel. Most importantly, she makes Ernest her heir — but not without a set of robust safeguards.

Because his parents were so stingy with their affection, Alethea sees that Ernest is starved for it. In fact, he’s so unused to affection that he can’t distinguish between genuine kindness and manipulation:

His . . . trustfulness in anyone who smiled pleasantly at him, or indeed was not absolutely unkind to him, made her more anxious about him than any other point in his character; she saw clearly that he would have to find himself rudely deceived many a time and oft before he would learn to distinguish friend from foe.

Ernest hasn’t learned Red Riding Hood’s wisdom from Sondheim’s Into the Woods: Nice is different than good. And so Alethea wills her fortune to Overton, to secretly hold in trust for Ernest until he reaches age 28. Notably, she does this fully expecting that Ernest will crash and burn, repeatedly, until he is entitled to her money:

I daresay I am wrong, but I think he will have to lose the greater part or all of what he has, before he will know how to keep what he will get from me.

And crash and burn is exactly what Ernest proceeds to do, in spectacular fashion. Buckling to his parents’ wishes, and under the influence of a newfound religious zeal, Ernest enters the clergy after college. Then, he:

loses his inheritance from his grandfather by entrusting it to his “friend” Pryer, a fellow clergyman who takes the money and runs.

loses his faith in Christianity conversing with a fellow tenant.

loses his reputation when he mistakenly believes another tenant to be a prostitute and makes advances on her, leading to his arrest and imprisonment.

loses his hope when, now an ex-convict, he marries the former servant, Ellen, and begins selling second-hand clothes with her. While the shop initially succeeds, Ellen is revealed to be an unrepentant alcoholic, and Ernest escapes the marriage only through a pretty contrived deus ex machina (she’s already married!).

All is related in humorous detail, and all is entirely in keeping with Butler’s use of evolutionary theory as a prism for viewing humanity. Essentially, Butler treats Ernest as a botanical specimen that, by being denied water (money) while being exposed to extremes, grows the deeper, stronger roots that will enable him to survive and thrive in a harsh world.

Withholding generational wealth is key to Butler’s framework. After all, throughout Ernest’s ordeals, Overton is trustee to Ernest’s inheritance, as well as a wealthy man in his own right. At any point, he can swoop in and rescue Ernest from his own mistakes — perhaps replacing the money Ernest foolishly allowed Pryer to steal, or, following Ernest’s release from prison, giving him funds to emigrate to America to start a new life. At any point, Overton can “water the plant”.

But Overton knows that swooping in and rescuing Ernest will only prolong his immaturity and deprive him of the wisdom he’ll need to manage his inheritance — which, in Overton’s hands, has now grown into a princely sum. The timing of generational wealth, Butler emphasizes, is everything. Certainly, Overton doesn’t shut the spigot off entirely; he never allows Ernest to fall into extreme poverty and gives him money to start a shop after serving his prison term. Nonetheless, Overton’s Darwinian strategy is to

keep a sharp eye upon Ernest as soon as he came out of prison, and let him splash about in deep water as best he could till I saw whether he was able to swim, or was about to sink.

Ultimately, Overton allows Ernest to struggle until the kid, understandably, falls into a deep depression following his separation from Ellen (by this point, incidentally, Ernest is father to two young children). Overton then determines Ernest has suffered enough and rehabilitates him by employing him, giving him lodging at his home, and taking him on a trip to Europe.

Eventually, Ernest’s despair lifts and he finds his footing — conveniently, just as he turns 28 and comes into his inheritance from Alethea. Having learned from experience just how easily money slips from one’s fingers, Ernest lives well but not lavishly. In what was a very weird and jarring turn for this reader, he places his children with a foster family to be raised. And he turns his attention to writing, becoming an author of essays that raise novel and clever challenges to the status quo.

So all’s well that ends well! Which brings me to my main criticism of Butler’s prescription for passing down generational wealth . . .

It’s All a Little Too Pat

In my opinion, Butler shoehorns the issue of generational wealth, as well as Ernest’s coming of age generally, into a too-rigid scheme of evolution. Yes, Ernest needed to be deceived in order to learn to be more circumspect. Yes, he needed to lose his faith in order to question whether his beliefs were truly his own or merely foisted upon him by others, particularly his parents. And yes, his hardships matured him.

But Ernest’s total transformation into a gentleman and successful writer upon receiving his inheritance strikes me as facile. It would be nice if costly mistakes and delusions were confined to our youth. It would be nice if generational wealth was somehow timed to pass to us precisely when those mistakes and delusions were behind us, and we never needed to rely on family money due to setbacks, self-inflicted or otherwise.

Instead, we’re annoyingly human, with mistakes and delusions tending to dog us throughout our lives, if (hopefully!) to a lesser extent as we age. And despite our best efforts, “shit happens”: divorce, job loss, sickness. Life isn’t — as it is for Ernest once he receives Alethea’s money — smooth sailing. (Tellingly, Butler doesn’t have Ernest remarry or take his children back from their foster family after he inherits his wealth. He goes on to live by and for himself.)

As such, Butler’s idea that a young adult can be perfectly “primed” by his environment to know himself and thus become entitled to generational wealth strikes me as wishful thinking.

Credit to Butler Where It’s Due

Even though I found Butler’s evolutionary framework awkward, The Way of All Flesh does contain wisdom as to how the older and younger generations should relate to one another. All of Ernest’s crashings-and-burnings do enable him to understand the world and, more importantly, himself, giving him the ability to navigate the future.

It’s an important insight, given that modern parenting — at least in the affluent, professional class — is so focused upon nurturing children from one achievement to the next. Childhood and adolescence has steadily become a carefully-supervised process of credential-building in preparation for college and beyond, with no room for failure. The Way of All Flesh suggests this makes for an educated young adult, but not a wise nor resilient one.

On the one hand, I think Butler would commend modern parents for paying for lessons and activities that align with and promote their children’s inborn talents and interests. But on the other, I think he’d also caution parents against over-structuring children’s environments, to the point of depriving kids of autonomy. Like Ernest, the young need to make their own mistakes in order to know their own minds. Some crashing-and-burning is in order if they are to develop those robust roots.

The questions for any parent are: How big the crash and how long the burn? Given today’s high-stakes college admissions competition, one flunked class is considered a catastrophe in some quarters.

And as to the issue of generational wealth, given the immense cost of college and a tight job market, are parents justified in demanding their kids major in certain subjects as a condition for paying for tuition? When her daughter announced she wanted to study psychology, my friend replied: “That’s very nice. And how are you going to pay for that?” Does that make my friend a realist who was helpfully looking out for her daughter’s best interests? (Her daughter earned a very practical nursing degree instead. She’s working and doing fine.) Or does that make her a teeny bit like George Pontifex? Would the answer be different if the daughter announced a desire to major in, say, Art History or East Asian studies?

If anything, The Way of All Flesh encourages parents to ask whether they are crossing the line from acting on behalf of their children to imposing their will in a way that steals agency. The line can be a blurry one.

Finally, despite Butler’s merciless satire of his parents’ generation, The Way of All Flesh encourages all of us, older and younger, parent and child, to be a bit more magnanimous towards one another. Millennials may mock Boomers for thinking you land a job by simply greeting potential employers with a firm handshake; Boomers may mock Millennials for thinking they’re entitled to a high salary and perks on their first real job. But Butler reminds us that, no matter how independent-minded we believe ourselves to be, we’re still products of our environment, shaped by the collective consciousness of our generation.

Such an interesting subject, one I've wrestled with. Two observations:

You can clearly see the wrong thing to do with children and money but it is very hard to see the right thing.

And children know how wealthy their parents are (some parents deceive themselves that they can disguise their wealth)so communication and transparency give you a chance to be more right than wrong.

Imagine a world in which generational wealth didn’t exist. Imagine also a world in which all young people had “enough” — they had good food, healthcare, decent lodging and as much education as they wanted/needed to live the lives they wanted to live.

I scrounged for food in college to a degree I myself can barely believe now. It didn’t grow my character — it just filled me with anxiety. I don’t know why anyone thinks poverty is good for you. It’s terrible.