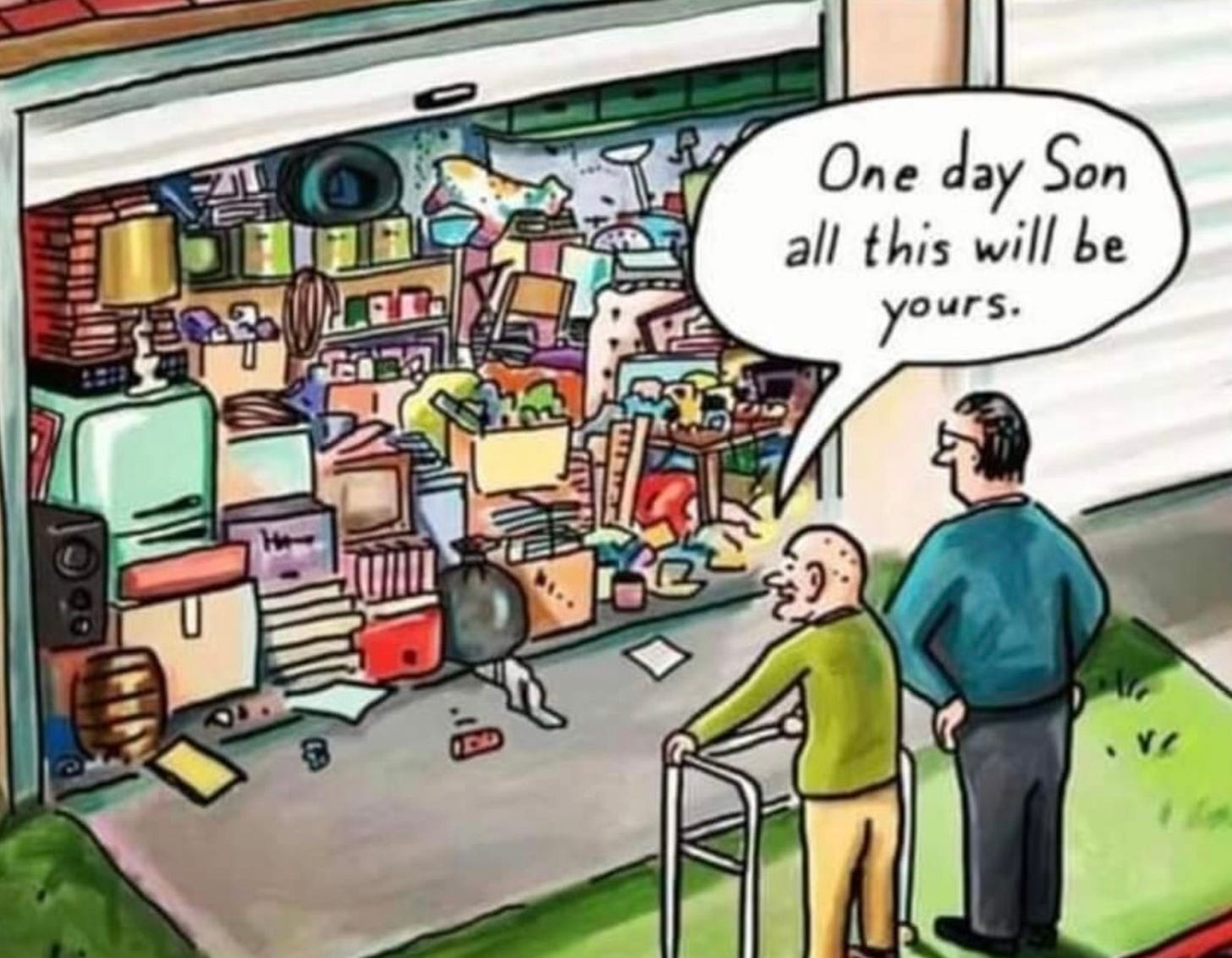

Out With the Old

The Midlife Rite of Passage is Getting Rid of Stuff

Last year I cleared out my parents’ house. It was a harrowing endeavor, and a poignant one, made possible only by massive amounts of help from my extended family and about a billion heavy-duty black trash bags.

Most people in my age cohort, Gen X, have already endured the clearing of their folks’ home, whether due to parental death or a move into assisted living. If you’re younger than Gen X, be forewarned: You, too, will one day stand before kitchen shelves lined with stacks of plastic take-out ware and think, Seriously, Mom and Dad? You really needed to save every container for every to-go meal you ever ordered?

It's astonishing how much one couple manages to acquire and retain over the course of eighty-odd years. The multiple sets of vintage table settings (does anyone actually use teacups and saucers?); the drawers crammed with specialty tools and parts (how many drill bits does one man need, Lord?); the acres of books and DVDs; the bins of Christmas lights and artificial holiday greenery – it’s all Stuff, and when you’re the one charged with somehow getting rid of it, it is endless.

Where does it all come from? When I cleaned out my folks’ place, I hypothesized the bulk of their Stuff accrued due to simple inertia. That theory would certainly explain the insane number of decorative wooden ducks. At one point, circa 1983, Mom bought one such duck on a whim. Then Dad forgot her birthday until the last minute, as he was wont to do. Panicked, he ran to the gift shop, spotted another wooden duck, and figured: She likes these! Score! So he gave her a second duck, then a third on their anniversary. At this point friends and secondary relatives noticed the proliferation and concluded Mom was some kind of duck fanatic. Wooden ducks became everyone’s unthinking gift for her, and before long, there was an entire beady-eyed flock perched along the mantel (nearly all of them Mallards).

Mom received each duck graciously and without complaint. But in private, she’d sometimes stare at the mantel with a defeated mien and sigh, What am I gonna do with all these damn ducks?

The answer, of course, was nothing.

Possessions As Placeholders

While the ducks were due to inertia, other objects my parents owned as symbolic placeholders, substitutes not only for people but for action, behavior, feeling. Once I understood this, I realized why my parents held on to so much, seemingly against all reason: It may have been just Stuff, but it was the next best thing to the Real Deal. Stand-ins, after all, stand in for something. They fill a void, often an aching one.

Placeholders for Those Lost

So many of Mom and Dad’s possessions first belonged to their parents, grand-parents, or those even further down the family tree. Two shelves of Mom’s china cabinet, for instance, were dedicated to vintage Hummels, those apple-cheeked porcelain figurines that now scream “granny” and “kitsch” (or, if you prefer, “Granny Kitsch”).

Mom did not like Hummels. She thought they were dumb. But her own mother adored them, and when she passed, Mom found she couldn’t give them away. My grandmother invested so much attention in selecting each figurine, took such pride in her Merry Wanderer and Umbrella Girl (if you know Hummels, you know), that disposing of them seemed to Mom like spurning her own flesh-and-blood. I should just donate them to goodwill, she once confided in me. But I’d feel so guilty.

I get it, because after cleaning out my folks’ place, I came home with a ceramic tile depicting a cat, mounted in a honey-oak frame Mom made in her wood-working class. The cat tile is not to my taste and neither is the honey-oak. But Mom crafted the frame and signed it on the reverse. It not only speaks to her living hands but to the person Mom was: preternaturally agreeable, sometimes to a fault. She had intended on taking a watercolor class, you see. But someone messed up her course registration, and when she found herself in wood-working instead, she cheerfully went along with it because she knew the instructor personally and “didn’t want to hurt his feelings” by bailing out.

And so now the cat tile sits in one of my drawers as I mull over where and if to hang it. It doesn’t fit with my décor in the least and believe me, I have plenty enough pictures on the wall as it is. But shedding it would somehow, painfully, feel like a renunciation of my mother, who now resides in memory care. These days I am clinging to the last vestiges of her, including the woman that, incredibly, took woodshop – thereby risking slicing off a finger or two – so as not to offend. Yep, the cat tile stays: my kids’ future problem, no doubt.

Placeholders for Action

A lot of my parents’ belongings were stand-ins for changes they hoped for but never summoned the effort to make. Dad, for instance, was overweight and unfit for decades before he passed. Yet not only did he keep an old wooden Nordic Track in his office, but one of those ab-roller wheels, too – which, if you ever saw the size and consistency of Dad’s gut, almost seems like an edgy, self-aware joke. Mom, likewise, held onto kitchen appliances she never touched, including an electric citrus juicer.

My parents bought the fitness equipment and the juicer believing they would use them. They simply mistook the objects themselves as magical, as having the ability to inspire their own use. Now that we’ve spent money on this Stuff, my parents probably figured, we’re not going to let it just sit there.

My parents expected the mere presence of the idle Nordic Track, the still-unboxed juicer, would serve as a spiritual rebuke to their indolence, spurring them to action. But what plainly happened was that the Stuff did not rebuke them – on the contrary, it just sat there. And in sitting there, the Stuff became totemic, symbolizing a Nordically-fit, juice-filled, yet oh-so-attainable future, a sweet tomorrow where Dad would tone his rock-hard abs on the roller then enjoy a glass of fresh-squeezed Florida orange with Mom. The Stuff became the substitute for action.

(I’m aware I’m sounding a bit snarky, but I’m in no position to judge my parents. I’ve made the same error of substituting Stuff for action. Witness my craft drawer, replete with all the brushes and needles and doo-dads for the projects I fully intend on completing . . . at some point.)

Placeholders for Love

Before Dad passed, when Mom’s dementia was really starting to set in, I would fly cross-country to check in on them. Around that time, Mom developed a nervous tick of hauling out objects and asking me if I wanted them. She had begun to lose the memory of how she acquired her possessions; as such, the things she owned started to appear alien and of supernatural origin, as if they had materialized in her closets and drawers out of thin air.

A lot of the belongings she tried to unload on me were pieces of jewelry I had gifted her over the years. Someone must have given me this, she’d say, holding out a necklace or ring I had carefully chosen for her. As if I’m ever going to wear that thing!

I found it both funny and sad. I didn’t care that Mom wasn’t a fan of some of my presents. But I was sorry – remorseful, even – that I had given her so much unwanted Stuff while withholding what she really wanted: myself. My sibling and I moved far away from our parents while in our twenties, and we had good reasons for doing so. Still, Mom felt our absence, dearly. I couldn’t have lived closer to home without losing my sanity, but I very well could have visited more often. The money I blew buying and mailing Mom meaningless gifts would have been better spent traveling to her.

Yet I convinced myself that it was never the right time for my husband and I to miss work, or for the kids to miss school. The logistics of packing up a family and flying cross-country for a visit are a pain in the ass (try booking an appropriate layover flight for a pair of three-year-olds, for instance, never mind finding a pet sitter to tolerate a Shih Tzu with OCD). And because the logistics are a pain in the ass, it was astonishingly easy for me to decide the visit itself wasn’t worth the trouble. Better to send Mom a nice bracelet instead, I reasoned – which is exactly what I did for her on Christmas, then a pair of earrings on her birthday, and so on and so forth over time until, one day, I was facing a drawer filled with all the jewelry I ever gave her and wondering what to do with it.

In the end, all those sparkly baubles amounted to a kind of fossil record of how, over the years, I couldn’t be bothered with the inconvenience of being with Mom. She wanted my time and attention, meaning she wanted my love, and instead I sent some silly pendant I ordered online.

I kept one of these pendants, a heart-shaped one. Although it looks cutesy, to me it signifies a hard truth: There are no genuine placeholders for love. Embrace and shoulder the bother of time and attention. The rest is just Stuff.

Really well-written and painfully true. Thanks Johanna.

Those Himmel figurines: I had never heard of them before but now I'm fascinated by them! They look shockingly like some of the sculptures Jeff Koons has made (but his are always somehow "off," somehow mocking or satirical instead of honestly sentimental).